Where are all the dwarfs?

Astronomers of the international CLUES collaboration have identified “Cosmic Web Stripping” as a new way of explaining the famous missing dwarf problem: the lack of observed dwarf galaxies compared with that predicted by the theory of Cold Dark Matter and Dark Energy.

High-precision observations over the last two decades have indicated that our Universe consists of about 75% Dark Energy, 20% Dark Matter and 5% ordinary matter. Galaxies and matter in the universe clump in an intricate network of filaments and voids, known as the Cosmic Web. Computer experiments on massive supercomputers have shown that in such a Universe a huge number of small “dwarf” galaxies weighing just one thousandth of the Milky Way should have formed in our cosmic neighbourhood. Yet only a handful of these galaxies are observed orbiting around the Milky Way. The observed scarcity of dwarf galaxies is a major challenge to our understanding of galaxy formation.

An international team of researchers has studied this issue within the Constrained Local UniversE Simulations project (CLUES). The CLUES simulations use the observed positions and peculiar velocities of galaxies within Tens of Millions of light years of the Milky Way to accurately simulate the local environment of the Milky Way. “The main goal of this project is to simulate the evolution of the Local Group - the Andromeda and Milky Way galaxies and their low-mass neighbours - within their observed large scale environment”, said Stefan Gottlöber of the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam.

Analysing the CLUES simulations, the astronomers have now found that some of the far-out dwarf galaxies in the Local Group move with such high velocities with respect to the Cosmic Web that most of their gas can be stripped and effectively removed. They call this mechanism “Cosmic Web Stripping”, since it is the pancake and filamentary structure of the cosmos that is responsible for depleting the dwarfs’ gas supply.

“These dwarfs move so fast that even the weakest membranes of the Cosmic Web can rip off their gas”, explained Alejandro Benítez LLambay, PhD student at the Instituto de Astronomía Teórica y Experimental of the Universidad Nacional de Córdoba in Argentina, and first author of the publication of this study. Without a large gas reservoir out of which to form stars, these dwarf galaxies should be so small and dim that they would be hardly be visible today. The missing dwarfs may simply be too faint to see.

The study of Benítez Llambay and colleagues is published in the February issue of Astrophysical Letters.

Information and further videos: https://www.clues-project.org/cms/images-and-movies/cosmic-web-stripping/

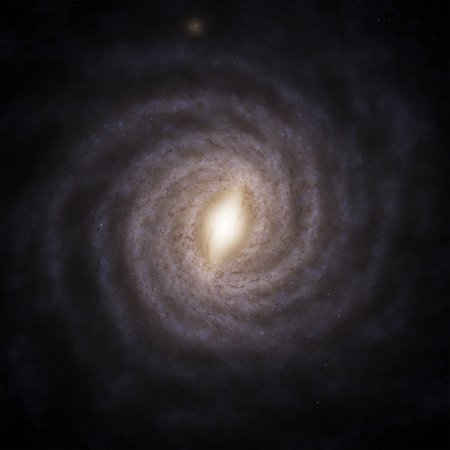

Cosmic Web Stripping removes gas from a very fast dwarf galaxy crossing the local web. The image is a visualization of a CLUES simulation. The arrow symbolizes the velocity oft he dwarf, located right below.

Credit: Alejandro Benítez Llambay

Zoom into the region where the dwarf is located.

Credit: Alejandro Benítez LlambayFurther information

Original publication

Alejandro Benítez Llambay, Julio F. Navarro, Mario G. Abadi, Stefan Gottlöber, Gustavo Yepes, Yehuda Hoffman, and Matthias Steinmetz: Dwarf galaxies and the Cosmic Web. 2013 ApJL 763 L41.

DOI: doi:10.1088/2041-8205/763/2/L41

Constrained Local UniversE Simulations (CLUES)

Images

Cosmic Web Stripping, Visualization.

Big screen size [1000 x 1000, 280 KB]

Original size [2000 x 2000, 390 KB]

Cosmic Web Stripping removes gas from a very fast dwarf galaxy crossing the local web. The image is a visualization of a CLUES simulation. The arrow symbolizes the velocity oft he dwarf, located right below.

Big screen size [1000 x 1000, 260 KB]

Original size [2000 x 2000, 370 KB]

Zoom into the region where the dwarf is located.

Big screen size [1000 x 1000, 160 KB]

Original size [2000 x 2000, 210 KB]

Videos

Information and further videos: https://www.clues-project.org/cms/images-and-movies/cosmic-web-stripping/